A key platform of anarchism is our conviction that it should be communities that determine their own affairs. This stands at odds with the liberal democratic vision, where a political elite is elected or appointed to make decisions on behalf of a collective, a vision that anarchists regard as a deep corruption of the entire concept of democracy. In other words, it is our firm belief that decisions regarding how a community is governed should be made exclusively by the community in question. As Emma Goldman famously argued, “no one is more qualified than you to decide how you live.” The livable city is one that is meaningful to its inhabitants, where they make the decisions that affect them and shape it in such a way that reflects their needs and wants.

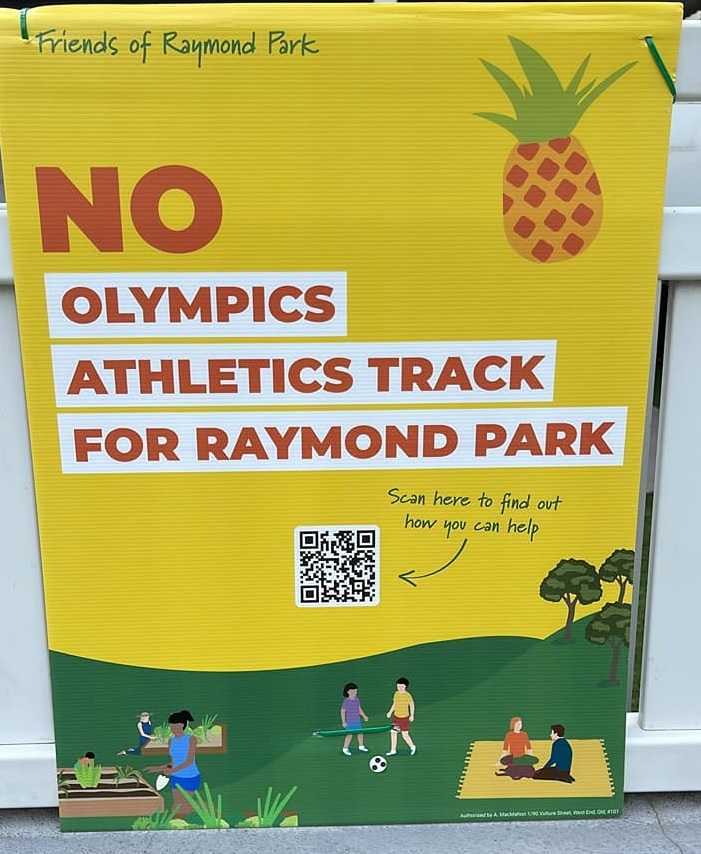

Raymond Park is a massive green space in the heart of Kangaroo Point. Often referred to fondly as Pineapple Park after the neighbouring Pineapple Hotel, the park was originally established in 1864 and has ever since been a home to the community’s sporting and recreational activities, representing half of Kangaroo Point’s green space. The park played an important role during protests to release 120 detainees from the nearby refugee detention centre on Main Road, hosting large mobilisations that lasted over a year. During the pandemic the park has seen a spike in popularity, green spaces having played a demonstrable role in maintaining the physical and mental well-being of people living in highly urbanised environments. It is, however, slated to be bulldozed to make way for a 17,000 m2 warm up track for the upcoming 2032 Olympics, along with several homes and trees over a hundred years old. The decision to make use of Raymond Park was made without any consultation with the Kangaroo Point community, having been “confirmed to be of suitable scale and dimension ... as part of the development of the 2032 Games submission for the International Olympic Committee.”1 According to Friends of Raymond Park spokesperson Melissa Occhipinti, residents in fact first heard of the plans through the media.2

Can we expect any sort of transparency in the decisions being made on behalf of the community however? According to Part 7 of the Brisbane Olympic and Paralympic Games Arrangements Bill 2021, passed without amendment in December last year, the Olympics organising committee will be exempt from the Right to Information Act, meaning that the answer is ‘no’. This contradicts the Queensland Government’s own Human Rights Act 2019, which claims to protect “the right of all persons to hold an opinion without interference and the right of all persons to seek, receive and express information and ideas”.3 Tellingly, according to a committee tasked with investigating the human rights implications of the Bill, there “has been no clear rationale or assurance provided ... that the exemptions to the Right to Information Act 2009 will not be used inappropriately.”4

This begs the question of how the public will be able to monitor the conversion of Raymond Park into a track compatible with the IAAF’s Track and Field Facilities Manual, which dictates that the “size of the land shall be at least twice as large and, if possible, three times as large as the required net sports area in order to be able to accommodate suitably landscaped areas between the sports spaces”. Despite assurances that there will be no resumptions of neighbouring houses, the dimensions of the track simply do not reflect this promise. This is only one of several mysteries that surround the future of the area, including how the East Brisbane State School, which sits directly next to the existing stadium, will be accommodated and what sort of arrangements will be made to avoid any disruption to students during the extensive renovation of the site that will take place over the course of several years to make way for the two week event. Friends of Raymond Park, a neighbourhood group formed in October last year, has already noted that a more appropriate venue exists in the nearby Giffin Park where it could potentially benefit the Coorparoo community well after the Games themselves without the destruction of existing homes and disruption to community activities.

Anarchist Communists Meanjin remains opposed to the Olympic project entirely however. While we understand that Brisbane’s public transport infrastructure is in need of a major overhaul, a common defence of the Games, we do not believe that the Olympics is necessary to accomplish this goal and we certainly do not believe in idiotic Elon Muskesque ideas like ‘flying taxis’. The proposal to build an air taxi hub in Moreton Bay for ‘airborne rideshares’ in time for the Olympics that, according to Skyportz chief executive Clem Newton-Brown, will be “somewhat more than a taxi but cheaper than a helicopter”5, is an insult to those already experiencing soaring rent prices. The insane cost of previous Olympics (Sydney 2000: US$4.7bn, London 2012: US$11bn, Beijing 2008: US$42bn) is an indication of the sheer enormity of the bill that Queensland tax-payers are being faced with. The demolition of the existing stadium and its replacement is already projected at AU$1bn.6

While it’s true that this venue is unlikely to fall into disuse following the Olympics like the 2010 World Cup stadium in Cape Town did, an enduring legacy of the 2032 Olympics will be a permanent surveillance state. While we have barely tolerated check-in apps and other security measures during the pandemic due to the extraordinary nature of the crisis, the Olympics promise to turn Brisbane into a permanent surveillance state, as they did with London following the 2012 Games. We likewise recall how the Brazillian state used the 2016 Summer Olympics to terrorise Rio de Janeiro’s poorer communities and the war that the Chinese state carried out against Beijing’s homeless in 2008. In 2018, Indigenous activists were harassed and attacked by police and far-right elements during the Commonwealth (Stolenwealth) Games while staging demonstrations demanding recognition of colonial genocide. The transformation of Brisbane into a total security state in the leadup to and during the protests against the G20 Leaders Summit in 2014, in which locals were arrested for not carrying ID, searched without suspicion and barred from carrying ‘prohibited’ items like eggs and canned tomatoes, also sets a precedent for the sort of state violence we can expect anyone protesting the Olympics are likely to face.7 Along with the unwanted $3bn Queen’s Wharf super-casino currently under construction, we can see that the Olympics and its associated projects are serving simply to transform Brisbane into a playground for the rich while forcing its inner city locals further out of town.

The Olympics, the casinos and all the other dross imposed on working class communities from above reflect the sterility and alienation of class-based society. In this struggle, the working class is currently in an inferior position, but this can be reversed if we fight back and gain a space we can call our own.

References:

-

^

Correspondence from Stirling Hinchcliffe MP to Cr Jonathan Sri, 1st Sept 2021.

-

^

https://tv.parliament.qld.gov.au/Committees?reference=C6210#parentVerticalTab3

-

^

https://documents.parliament.qld.gov.au/TableOffice/TabledPapers/2021/5721T1992.pdf

-

^

Ibid.

-

^

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-14/flying-taxi-hub-brisbane-olympics-2032/100538016

-

^

https://brisbanedevelopment.com/new-1b-stadium-gabba-to-be-rebuilt-as-main-olympic-stadium/

- ^