On July 25, 2023, workers walked off Brisbane's massive Cross River Rail project, voting to stop work until the following week. This decision came in the wake of a catastrophic safety failure at the Boggo Road site, where a worker fell over 12 metres from scaffolding and was rushed to the hospital. The injured scaffolder, Nation "Nash" Kouka, remains hospitalised after his near-fatal fall.

The Cross River Rail project, outsourced by the government to the private company CPB Contractors, has been grappling with numerous Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) issues. Notably, the Gabba location has seen the release of dangerous silica dust, posing risks not only to the workers but also to the public. According to on-site workers, accidents and near misses are common.

On the same day as the above accident, a metal rod plummeted from some scaffolding, rebounding into the cockpit of a forklift. Fortunately, no injuries occurred, yet this incident serves as a testament that such occurrences are not isolated. Despite these notices, the hazardous work environment persists. This confirms the suspicions held by most workers in the construction industry: even if they were to report safety breaches, the government agencies responsible for enforcing the laws are failing to make sure bosses actually rectify safety issues.

Workers have made their concerns over OHS clear to their bosses, but CPB insisted on putting profits over worker safety and refused to listen. The consequences of CPB negligence have been catastrophic.

Compounding the issue is the fact that CPB has found an ally in their negligence in the Australian Workers Union (AWU). In order to prevent the militant CFMEU from effectively standing up for worker safety, CPB has appointed AWU as the official site representatives.This arrangement protects CPB profits because, as reported by former AWU members at Cross River Rail, AWU officials have been totally uninvolved in worker’s struggles to resolve important OHS issues - and workers who are not backed by the collective power of a union are easily ignored. CPB's negligence has extended to interfering with CFMEU union officials' attempts to inspect the sites, hindering the resolution of OHS issues.

Amid the July work stoppage, CPB hastily announced a "safety reset" in an effort to regain control of the situation. Workers were instructed to return to the site less than two days after the accident to participate in the “reset.” CPB leveraged pressure on individual workers and the contractors employing them, attempting to compel the workforce's return. Unwavering in their determination, workers stood firm, remaining off-site until Monday, with the union mobilising to make sure the stopwork decision was adhered to across all sites. This sent a clear message that they were united and prepared to take safety into their own hands. With the return to work on Monday workers began the safety reset on their own terms, supported by their union.

With the media spotlight fading, CPB Contractors began to drag their feet in collaborating with CFMEU officials on the safety reset. This has stalled the project, as workers were unwilling to work in dangerous sections. On August 8, 2023, the CFMEU publicised these unresolved issues.

- Scaffolding that was not up to safety standards

- Risk of falling objects from heights

- A serious silica dust issue

- Structural integrity issues

- Serious electrical safety issues

- Many unqualified workers who were working with little training

Workers are standing strong, staying in the smoko hut until their workplace is safe. This collective resolve to stand up against their employers will triumph in winning a safe working environment, a feat that the government agency responsible for OHS oversight has failed to achieve.

OHS on the balance sheet

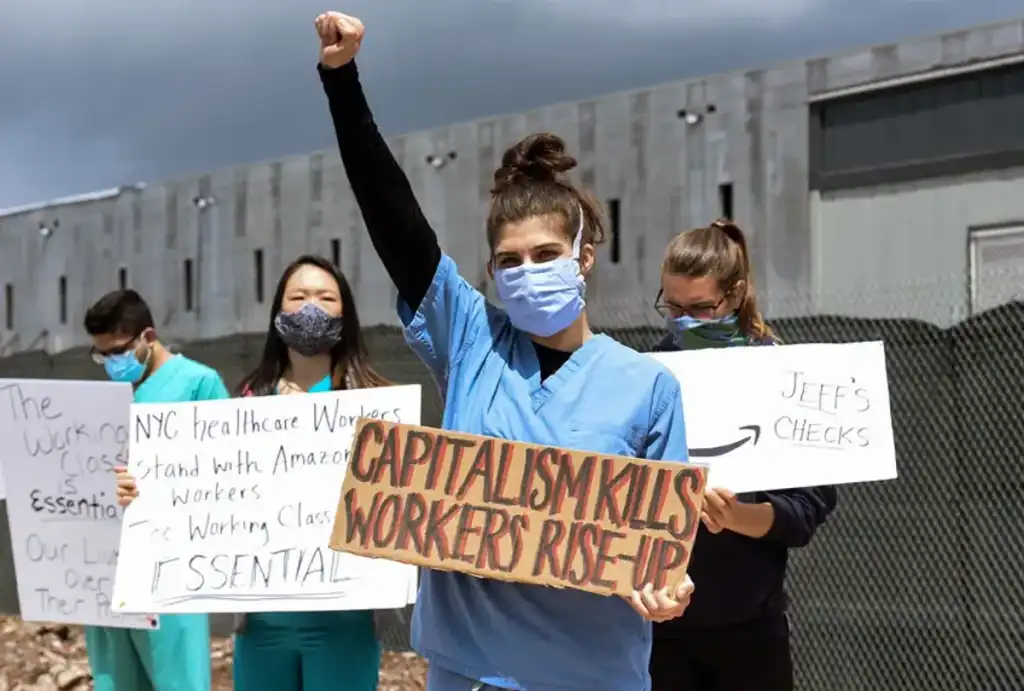

Let's be clear: the driving force behind these OHS issues is profit. The bosses seek to maximise productivity while minimising expenses, including those required for worker safety. Cutting corners on equipment and personal protective gear leads to dangerous accidents, and proper training is often overlooked in the pursuit of higher profits. The logic of capitalism dictates that in order to raise profits, the bosses will inevitably cut costs by skimping on OHS issues.

On the other side of the equation, bosses want to get as much work out of us as possible. Fatigue and working at unsafe speeds due to demanding schedules and speed-ups further contribute to safety issues. These practices compromise the well-being of workers, chronically exhausting them, leading to mistakes and accidents that could otherwise be avoided. Both long shifts and speed-ups are ways the bosses try to milk every bit of productivity out of us.

Unsafe work has a profit motive.

While the profit motive undeniably causes innumerable problems, it also bestows upon us a degree of power.In order to extract profit from us, bosses depend on our continued labour. While one or two workers might be replaced if they individually refuse to work in an unsafe environment, a united workforce poses a greater challenge, compelling employers to negotiate or risk an expensive battle. It's true that OHS issues arise from this exploitative profit extraction, but organised workers have the capacity to unite in the fight for safety.

OHS fights in the past: Safety at SGIO

It is important to look to related struggles to assess where workers have succeeded and failed in the past. The following is an account from Humphrery McQueen’s Frameworks of Flesh on a struggle during the construction of the State Government Insurance Office (SGIO) building in the Brisbane CBD.

“Jim Young fell eight storeys to his death on the Queensland SGIO site in July 1968. Stoppages began at once around the city as the men walked off for 12 hours. The building unions campaigned for enforcement, which the Department of Labour and the MBA impeded. The unions’ call for safety officers met with “a blank refusal”. The issue remained alive until an inspector determined the situation in favour of the SGIO workers. The Branch Executive welcomed the victory as good in principle because the demands had been accepted by the boss. They criticised the conduct of the struggle because the members had not told the office about the problem until the stoppage was under way. Although the rule was that even the smallest dispute had to be notified, the officials were becoming more responsive and flexible to protect their members and to preserve their own authority.

The SGIO dispute happened just in time for Branch officials to raise at the Rockhampton Safety Convention on 29-30 July 1968. One organiser afterwards accused the employers of attending for “the sole reason of pulling the union policy to pieces.” The union delegates got no chance to ask hard questions because all queries had to be submitted in writing and the embarrassing ones were never read out. Secretary Delaney complained that “many pious resolutions had been carried at conventions but were forgotten immediately after.

Conditions at the SGIO job confirmed Delaney’s assessment. Although the client had charge of the State’s system of workers’ compensation, the safety for its new building was a disgrace. SGIO labourers became even more union-minded after the transfer of their delegate. A few days later, the death of Bro. Harmer led to a further walk-off before all the city’s building workers marched on Parliament House. They went out again on 27 November 1968 to press for safety committees. Most employers were either against their establishment, or insisted on nominating the membership. Early in 1969, the men at SGIO elected their own safety officers.

Another death at the SGIO site in June provoked a third and protracted stoppage. The contractor and the MBA still opposed allowing workers any say in the choice of a safety officer. The men stayed out. The union wanted the firm to be charged with manslaughter. By 30 June, collections on other jobs had brought in $2,000 for the strikers; on Saturdays, the Branch distributed food parcels valued at $15 each. The Commissioner agreed that men should have some say in the selection of their safety officer, and the firm conceded that the job needed cleaning up. Then, a dispute erupted over the sacking of a BL delegate. Job action got him reinstated. When bricks began popping out of walls in February 1970, the BLs refused to work on the SGIO plaza. Concern over safety became a catalyst for rank-and-file control around the sites.

The payment of height money muddied the education of labourers in the battle for safety. The employers argued that they were paying extra for labourers to take risks. In turn, men who got that bonus were less likely to insist on protections. The unions saw multi-storey allowances as a way to improve the weekly wage. When the height allowance was at a flat-rate, it brought the earnings of labourers closer to those of tradesmen. Safety could seem secondary.”

OHS involves everyone

When some people think about OHS they think it’s solely about dangerous, blue-collar type work. OHS issues go beyond physical injuries and can also encompass mental health and safety from harassment.

Mental health is often individualised by employers, despite many mental issues stemming from the workplace. While modern companies are more likely to pay lip service to mental health, maintaining an ever increasing profit margin requires keeping workers in line with little pay, worsening working conditions, and harsh management. Company "solutions" tend to address symptoms rather than root causes, promoting self-care in your own time and asking coworkers “R U OK?" once a year. Some “progressive” companies may even allow for paid therapy sessions, cementing the idea that distress caused by poor working conditions is a sign of personal failing and a need for self-improvement, rather than a problem of working conditions. This approach serves as both propaganda and a means to evade the work of seriously addressing mental health in the workplace.

As an example of an OHS dispute centred about mental wellbeing, last year workers at Melbourne Dangerfield organised to demand safety from the regular harassment they received from customers. They, along with their union RAFFWU, picketed the store to demand a full-time security guard. They were successful in this campaign for workers' health and safety.

Where to from here?

OHS laws are all well and good, but unless we organise ourselves with our coworkers to fight to enforce them they are just words on paper. Our collective power is the sole guarantee that we’ll keep coming home to our families. To achieve this,we need to talk to our coworkers to identify and address the OHS issues that matter most to them and how to demand better working conditions from the bosses. The creation of health and safety committees can be helpful, but they need to be backed up by the whole workforce.

We should demand more from our unions in the support they give us in our fight for safety. Regrettably, unions like the AWU are commonplace,with ineffective organisers, long wait times for support, and a conciliatory position towards the boss. Members of such unions must hold officials accountable, while ultimately understanding they need to rely on their own initiative and solidarity. If unions fail to provide workplace organising training and OHS legal information, it will be up to members to organise to share this information amongst themselves. Safety is a life and death issue, and we cannot wait for conciliatory unions to fix our problems.

While good union officials do exist, we can’t rely on them. While bosses fear militant union officials, what they fear even more is a well organised workforce that is involved in maintaining their conditions at work. Officials can provide invaluable experience and legal knowledge, but without that on the ground organisation their abilities to intervene will be limited. The fight for safety can only be waged by the workers it affects.

Where laws do not exist we will need to fight on the shopfloor to pressure the government to make OHS reforms. An example of this is the recently announced ban by the CFMEU on manufactured stone. Workers in Queensland who have handled this product have had a 1 in 5 chance of being diagnosed with silicosis, a fatal lung condition. The union has called on the ALP to ban manufactured stone but if protections are not passed through parliament the CFMEU will enforce a ban on the product across their sites. Workers will not touch the killer stone f it is brought on site. This action will put pressure on companies and the government to push through legislation banning the deadly stone. Where governments fail, workers' action will win our safety.

In the context of CPB, we need to use our collective power as a class to keep those responsible accountable. Rallies, strikes, riots. Nothing is off the table when we’re talking about a worker seriously injured by negligence. Workers voting to walk off the unsafe site is a proud example of how we can flex our collective power and remind the bosses that they need us more than we need them.